Written by Anita Dai, Primary Art Teacher (Year 1 and 2)

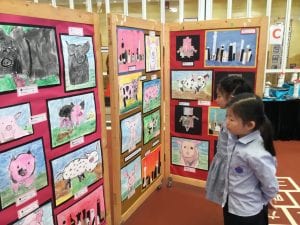

The last week of March saw the red courtyard transformed into a magical and colourful gallery showcasing the artwork of the YCIS Pudong Primary students based at Regency Park Campus. Thank you to all the parents who came and supported the Art Show! We hope everyone enjoyed looking at all the delightfully creative pieces. Also, an enormous and heartfelt THANK YOU to all the parents who volunteered their time to help with the mounting, set-up, and take-down of the Art Show. With your help, what seemed an arduous and ominous amount of work was easily and happily completed!

On the Wednesday of the Art Show, many students had the chance to show off their artwork to their parents after their Student Led Conferences. Of course, most parents happily expressed how impressed they were and there were many proud photos taken. Thank you to all for your enthusiasm! In fact, this is a very special opportunity, not just to give positive feedback, but to help your child develop a healthy attitude towards learning and problem solving. How? When you engage your child in conversation about Art, the opportunities for extension are endless.

On the Wednesday of the Art Show, many students had the chance to show off their artwork to their parents after their Student Led Conferences. Of course, most parents happily expressed how impressed they were and there were many proud photos taken. Thank you to all for your enthusiasm! In fact, this is a very special opportunity, not just to give positive feedback, but to help your child develop a healthy attitude towards learning and problem solving. How? When you engage your child in conversation about Art, the opportunities for extension are endless.

One of the best ways to begin a conversation about your child’s artwork is to ask about HOW he or she made the piece. This allows the child to go through a fairly neutral process of recall, which is a great way for your child to retain the learned skill. Take for example the Year 2 Secret Shadow Portraits. The portraits were displayed on a rotating cylinder and were only visible some of the time. Most students and even some teachers had no idea how it worked. Because the Year 2 students made the artwork, they could explain how the drawings were done on a transparent sheet, and they only appeared when the light inside the cylinder shone through and cast a shadow on the white paper in front of it. Challenging your child to explain that will truly imprint in their minds how light and shadow can be used to make Art.

After your child describes some of the steps for making the artwork, you might want to move on to a higher-order thinking question. “What do you think of your artwork?” It is important to allow your child to take the lead because then you will learn more about their thoughts and feelings. If you go ahead and offer your opinion first, your child might be hesitant to point out what he or she truly thinks. Take for example the Year 4 Gustav Klimt Tree paintings. Your child may have certain parts where he or she struggled, but if you start the conversation by saying, “That’s sooo great!” he or she may not want to disappoint you by bringing attention to any weaknesses. Imagine, however, if your child felt comfortable explaining how difficult the brush technique was, how he or she had to change the pressure when using the paintbrush to make the swirls go from a wider width to one increasingly more narrow and ending with a point. He or she might show you the branches that were done first and point out to you how improved the ones that were done later. This not only cements their learning of a new technique, it reinforces the growth mindset that is so important for all students.

After your child describes some of the steps for making the artwork, you might want to move on to a higher-order thinking question. “What do you think of your artwork?” It is important to allow your child to take the lead because then you will learn more about their thoughts and feelings. If you go ahead and offer your opinion first, your child might be hesitant to point out what he or she truly thinks. Take for example the Year 4 Gustav Klimt Tree paintings. Your child may have certain parts where he or she struggled, but if you start the conversation by saying, “That’s sooo great!” he or she may not want to disappoint you by bringing attention to any weaknesses. Imagine, however, if your child felt comfortable explaining how difficult the brush technique was, how he or she had to change the pressure when using the paintbrush to make the swirls go from a wider width to one increasingly more narrow and ending with a point. He or she might show you the branches that were done first and point out to you how improved the ones that were done later. This not only cements their learning of a new technique, it reinforces the growth mindset that is so important for all students.

Sometimes it is hard to approach these colourful and detailed paintings and not be amazed. Take for example the very professional-looking Jackson Pollock Action Paintings created by the Year 1 students. Especially when we know it is a five-year old who created them, we are all extremely impressed. Remember, however, praising a piece of artwork as “good” or “beautiful” will not help your child develop a growth mindset. Receiving praise makes people feel so good, they become addicted to it and will be motivated to try to get more of the same. When someone makes Art in order to receive praise, it can reduce his or her creativity. Instead of carefreely taking risks, the young artist becomes more concerned with the end product and how it will look. This leads to a copycat approach to making art. It can also end up with students drawing the same sort of thing over and over again. Thus, instead of having the results of boosting your child’s confidence, praise actually increases insecurity and limits your child to only engaging in things in which he or she has previously experienced success. This does not mean you cannot provide positive feedback. On the contrary, positive feedback is very important. It is general praise that is detrimental. Specific comments are very helpful AND they make the child feel like a superstar. For example, “The colours you chose work very well because it makes this area really POP out!” This is the kind of useful feedback that the student can take and apply to a new piece of artwork. Alternatively, you can talk about the effect of the artwork, “When I look at this painting, it makes me feel very calm and relaxed.” This has the potential to start an entirely new conversation about why, which colours or lines or shapes feel calm, which ones feel different and why . . . the possibilities are endless.

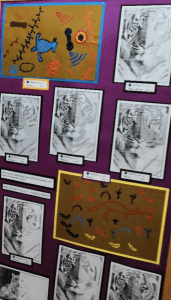

Sometimes when we look at Art, our first instinct is to try to find something we recognize. As an evolutionary response, it is an automatic and natural instinct to try to identify and name what we are looking at. When looking at Art, however, it can be unhelpful and irrelevant to ask your child, “What is it?” If your child is trying to draw something representational and you do not recognize what it is, hearing that question will crush his or her soul. If, like in the case of the Year 3 Aboriginal Art Dot Paintings, a parent asks, “What is it?” the question implies that Art is about reproducing an image so it is recognizable. Representational Art is only one of the many ways to make Art. The dot paintings are another kind of art where the dots form different symbols which have significant meanings. Thus, instead of limiting your child’s understanding of what constitutes art, consider asking your child, “What does this make you think of?” or “What is the history of this kind of painting?”

It is not easy to switch over to this type of reaction when looking at your child’s artwork. If you find it awkward, just make some appreciative noises, like “Oooh” and “Aaah” until you think of an appropriate question to ask. The great thing is you can be as creative as you like when you ask the questions. Here are some examples of quirky questions that will tickle your child’s imagination.

“What would it feel like if you could climb into this painting?”

“What title would you give this painting?”

“Make a circle with your thumb and finger. Put the circle on your favourite part of this piece of Art. Explain why.”

Whatever question you choose, when you engage in a conversation about their artwork, students benefit in so many ways. They know you are interested in what they think. They have a chance to reinforce their learning. They can extend their understanding of Art principles. And most importantly, they develop a healthy attitude towards learning where they understand that learning is a process that everyone goes through, and that the goal is not perfection, but improvement.